- Home

- Kurt Jr. Vonnegut

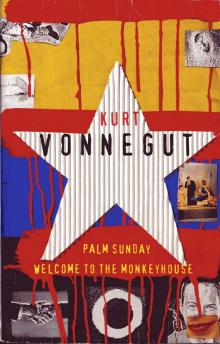

Palm Sunday, Welcome to the Monkey House Page 12

Palm Sunday, Welcome to the Monkey House Read online

Page 12

"The dog busted it," said Bullard. " 'Mr. Edison, sir,' I said, 'what's that red mark mean?' " 'My boy,' said Edison, 'it means that the instrument is broken, because that red mark is me.'"

"I'll say it was broken," said Bullard.

The stranger said gravely, "But it wasn't broken. No, sir. Edison checked the whole thing, and it was in apple-pie order. When Edison told me that, it was then that Sparky, crazy to get out, gave himself away."

"How?" said Bullard, suspiciously.

"We really had him locked in, see? There were three locks on the door—a hook and eye, a bolt, and a regular knob and latch. That dog stood up, unhooked the hook, pushed the bolt back and had the knob in his teeth when Edison stopped him."

"No!" said Bullard.

"Yes!" said the stranger, his eyes shining. "And then is when Edison showed me what a great scientist he was. He was willing to face the truth, no matter how unpleasant it might be.

" 'So!' said Edison to Sparky. 'Man's best friend, huh? Dumb animal, huh?'

"That Sparky was a caution. He pretended not to hear. He scratched himself and bit fleas and went around growling at rat-holes—anything to get out of looking Edison in the eye.

" 'Pretty soft, isn't it, Sparky?' said Edison. 'Let somebody else worry about getting food, building shelters and keeping warm, while you sleep in front of a fire or go chasing after the girls or raise hell with the boys. No mortgages, no politics, no war, no work, no worry. Just wag the old tail or lick a hand, and you're all taken care of.'

" 'Mr. Edison,' I said, 'do you mean to tell me that dogs are smarter than people?'

" 'Smarter?' said Edison. 'I’ll tell the world! And what have I been doing for the past year? Slaving to work out a light bulb so dogs can play at night!'

"'Look, Mr. Edison,' said Sparky, 'why not—'"

"Hold on!" roared Bullard.

"Silence!" shouted the stranger, triumphantly. " 'Look, Mr. Edison,' said Sparky, 'why not keep quiet about this? It's been working out to everybody's satisfaction for hundreds of thousands of years. Let sleeping dogs lie. You forget all about it, destroy the intelligence analyzer, and I'll tell you what to use for a lamp filament.'"

"Hogwash!" said Bullard, his face purple.

The stranger stood. "You have my solemn word as a gentleman. That dog rewarded me for my silence with a stock-market tip that made me independently wealthy for the rest of my days. And the last words that Sparky ever spoke were to Thomas Edison. 'Try a piece of carbonized cotton thread,' he said. Later, he was torn to bits by a pack of dogs that had gathered outside the door, listening."

The stranger removed his garters and handed them to Bui-lard's dog. "A small token of esteem, sir, for an ancestor of yours who talked himself to death. Good day." He tucked his book under his arm and walked away.

(1953)

NEW DICTIONARY

I WONDER NOW what Ernest Hemingway's dictionary looked like, since he got along so well with dinky words that everybody can spell and truly understand. Mr. Hotchner, was it a frazzled wreck? My own is a tossed salad of instant coffee and tobacco crumbs and India paper, and anybody seeing it might fairly conclude that I ransack it hourly for a vocabulary like Arnold J. Toynbee's. The truth is that I have broken its spine looking up the difference between principle and principal, and how to spell cashmere. It is a dear leviathan left to me by my father, "Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language," based on the "International Dictionary" of 1890 and 1900. It doesn't have radar in it, or Wernher von Braun or sulfathiazole, but I know what they are. One time I actually took sulfathiazole.

And now I have this enormous and beautiful new bomb from Random House. I don't mean "bomb" in a pejorative sense, or in any dictionary sense, for that matter. I mean that the book is heavy and pregnant, and makes you think. One of the things it makes you think is that any gang of bright people with scads of money behind them can become appalling competitors in the American-unabridged-dictionary industry. They can make certain that they have all the words the other dictionaries have, then add words which have joined the language since the others were published, and then avoid mistakes that the others have caught particular hell for.

Random House has thrown in a color atlas of the world, as well, and concise dictionaries of French, Spanish, German, and Italian. And would you look at the price? And, lawsy me, Christmas is coming.

When Mario Pei reviewed the savagely-bopped third revised edition of the "Merriam-Webster" for The Times in 1961, he complained of the "residual prudishness" which still excluded certain four-letter words, "despite their copious appearance in numerous works of contemporary 'literature' as well as on rest-room walls." Random House has satisfied this complaint somewhat. They haven't included enough of the words to allow a Pakistani to decode "Last Exit to Brooklyn," or "Ulysses," either —but they have made brave beginnings, dealing, wisely I think, with the alimentary canal. I found only one abrupt verb for sexually congressing a woman, and we surely have Edward Albee to thank for its currency, though he gets no credit for it. The verb is hump, as in "hump the hostess."

If my emphasis on dirty words so early in this review seems childish, I can only reply that I, as a child, would never have started going through unabridged dictionaries if I hadn't suspected that there were dirty words hidden in there, where only grownups were supposed to find them. I always ended the searches feeling hot and stuffy inside, and looking at the queer illustrations—at the trammel wheel, the arbalest, and the dugong.

Of course, one dictionary is as good as another to most people, who use them for spellers and bet-settlers and accessories to crossword puzzles and Scrabble games. But some people use them for more than that, or mean to. This was brought home to me only the other evening, whilst I was supping with the novelist and short-story writer, Richard Yates, and Prof. Robert Scholes, the famous praiser of John Earth's "Giles Goat-Boy." Yates asked Scholes, anxiously it seemed to me, which unabridged dictionary he should buy. He had just received a gorgeous grant for creative writing from the Federal Gumment, and the first thing he was going to buy was his entire language between hard covers. He was afraid that he might get a clunker—a word, by the way, not in this Random House job.

Scholes replied judiciously that Yates should get the second edition of the "Merriam-Webster," which was prescriptive rather than descriptive. Prescriptive, as nearly as I could tell, was like an honest cop, and descriptive was like a boozed-up war buddy from Mobile, Ala. Yates said he would get the tough one; but, my goodness, he doesn't need official instructions in English any more than he needs training wheels on his bicycle. As Scholes said later, Yates is the sort of man lexicographers read in order to discover what pretty new things the language is up to.

To find out in a rush whether a dictionary is prescriptive or descriptive, you look up ain't and like. I learned this trick of horseback logomachy from reviews of the "Merriam-Webster" third edition. And here is the rundown on ain't: the "Merriam-Webster" first edition says that it is colloquial or illiterate, the second says it is dialect or illiterate, and the third says that ain't is, "though disapproved by many and more common in less educated speech, used orally… by many cultivated speakers esp. in the phrase ain't I." I submit that this nation is so uniformly populated by parvenus with the heebie-jeebies that the phrase ain't I is heard about as frequently as the mating cry of the heath hen.

Random House says this about ain't: "Ain't is so traditionally and widely regarded as a nonstandard form that it should be shunned by all who prefer to avoid being considered illiterate. Ain't occurs occasionally in the informal speech of some educated users, especially in self-consciously [sic] or folksy or humorous contexts (Ain't it the truth! She ain't what she used to be!), but it is completely unacceptable in formal writing and speech. Although the expression ain't I is perhaps defensible— and it is considered more logical than aren't I? and more euphonious than amn't I?—the well-advised person will avoid any use of ain't." How's that for advice to parve

nus?

My mother isn't mentioned, but what she taught me to say in place of ain't I? or aren't I? or amn't I? was am I not? Speed isn't everything. So I lose a micro-second here and there. The main thing is to be a graceful parvenu.

As for the use of like as though it were interchangeable with as: "M-W-i" says, "The use of like as a conjunction meaning as (as, Do like I do), though occasionally found in good waiters, is a provincialism and contrary to good usage." "M-W-z" says that the same thing "is freely used only in illiterate speech and is now regarded as incorrect." "M-W-3" issues no warnings whatsoever, and flaunts models of current, O.K. usage from the St. Petersburg (Fla.) Independent, "wore his clothes like he was… afraid of getting dirt on them," and Art Linkletter, "impromptu programs where they ask questions much like I do on the air." "M-W-3," incidentally, came out during the dying days of the Eisenhower Administration, when simply everybody was talking like Art Linkletter.

Random House, in the catbird seat, since it gets to recite last, declares in 1966, "The use of like in place of as is universally condemned by teachers and editors, notwithstanding its wide currency, especially in advertising slogans. Do as I say, not as I do does not admit of like instead of ay. In an occasional idiomatic phrase, it is somewhat less offensive when substituted for as if (He raced down the street like crazy), but this example is clearly colloquial and not likely to be found in any but the most informal written contexts." I find this excellent. It even tells who will hurt you if you make a mistake, and it withholds aid and comfort from those friends of cancer and money, those greedy enemies of the language who teach our children to say after school, "Winston tastes good like a cigarette should."

Random House is damned if it will set that slogan in type.

As you rumple through this new dictionary, looking for dirty words and schoolmarmisms tempered by worldliness, you will discover that biographies and major place names and even the names of famous works of art are integrated with the vocabulary: A Streetcar Named Desire, Ralph Ellison, Mona Lisa, Kiselevsk. I worry about the biographies and the works of art, since they seem a mixed bag, possibly locked for all eternity in a matrix of type. Norman Mailer is there, for instance, but not William Styron or James Jones or Vance Bourjaily or Edward Lewis Wallant. And are we to be told throughout eternity this and no more about Alger Hiss: "born 1904, U.S. public official"?

And why is there no entry for Whittaker Chambers? And who promoted Peress?

It is the biographical inclusions and exclusions, in fact, which make this dictionary an ideal gift for the paranoiac on everybody's Christmas list. He will find dark entertainments without end between pages i and 2,059. Why are we informed about Joe Kennedy, Sr., and Jack and Bobby, but not about Teddy or Jacqueline? What is somebody trying to tell us when T. S. Eliot is called a British poet and W. H. Auden is called an English poet? (Maybe the distinction aims at accounting for Auden's American citizenship.) And when Robert Welch., Jr., is tagged as a "retired U.S. candy manufacturer," is this meant to make him look silly? And why is the memory of John Dillinger perpetuated, while of Adolf Eichmann there is neither gibber nor squeak?

Whoever decides to crash the unabridged dictionary game next—and it will probably be General Motors or Ford—they will winnow this work heartlessly for bloopers. There can't be many, since Random House has winnowed its noble predecessors. The big blooper, it seems to me, is not putting the biographies and works of art in an appendix, where they can be cheaply revised or junked or added to.

Have I made it clear that this book is a beauty? You can't beat the contents, and you can't beat the price. Somebody will beat both sooner or later, of course, because that is good old Free Enterprise, where the consumer benefits from battles between jolly green giants.

And, as I've said, one dictionary is as good as another For most people. Homo Americanus is going to go on speaking and writing the way he always has, no matter what dictionary he owns. Consider the citizen who was asked recently what he thought of President Johnson's use of the slang expression "cool it" in a major speech:

"It's fine with me," he replied. "Now's not the time for the President of the United States to worry about the King's English. After all, we're living in an informal age. Politicians don't go around in top hats any more. There's no reason why the English language shouldn't wear sports clothes, too. I don't say the President should speak like an illiterate. But 'cool it' is folksy, and the Chief Executive should be allowed to sound human. You can't be too corny for the American people—all the decent sentiments in life are corny. But linguistically speaking, Disraeli is dullsville."

These words, by the way, came from the larynx of Bennett Cerf, publisher of "The Random House Dictionary of the English Language." Moral: Everybody associated with a new dictionary ain't necessarily a new Samuel Johnson.

(1967)

NEXT DOOR

THE OLD HOUSE was divided into two dwellings by a thin wall that passed on, with high fidelity, sounds on either side. On the north side were the Leonards. On the south side were the Hargers.

The Leonards—husband, wife, and eight-year-old son—had just moved in. And, aware of the wall, they kept their voices down as they argued in a friendly way as to whether or not the boy, Paul, was old enough to be left alone for the evening.

"Shhhhh!" said Paul's father.

"Was I shouting?" said his mother. "I was talking in a perfectly normal tone."

"If I could hear Harger pulling a cork, he can certainly hear you," said his father.

"I didn't say anything I'd be ashamed to have anybody hear." said Mrs. Leonard.

"You called Paul a baby," said Mr. Leonard. "That certainly embarrasses Paul—and it embarrasses me."

"It's just a way of talking," she said.

"It's a way we've got to stop," he said. "And we can stop treating him like a baby, too—tonight. We simply shake his hand, walk out, and go to the movie." He turned to Paul. "You're not afraid—are you boy?"

"I'll be all right," said Paul. He was very tall for his age, and thin, and had a soft, sleepy, radiant sweetness engendered by his mother. "I'm fine."

"Damn right!" said his father, clouting him on the back. "It'll be an adventure."

"I'd feel better about this adventure, if we could get a sitter," said his mother.

"If it's going to spoil the picture for you," said his father, "let's take him with us."

Mrs. Leonard was shocked. "Oh—it isn't for children."

"I don't care," said Paul amiably. The why of their not wanting him to see certain movies, certain magazines, certain books, certain television shows was a mystery he respected—even relished a little.

"It wouldn't kill him to see it," said his father.

"You know what it's about," she said.

"What is it about?" said Paul innocently.

Mrs. Leonard looked to her husband for help, and got none. "It's about a girl who chooses her friends unwisely," she said.

"Oh," said Paul. "That doesn't sound very interesting."

"Are we going, or aren't we?" said Mr. Leonard impatiently. "The show starts in ten minutes."

Mrs. Leonard bit her lip. "All right!" she said bravely. "You lock the windows and the back door, and I'll write down the telephone numbers for the police and the fire department and the theater and Dr. Failey." She turned to Paul. "You can dial, can't you, dear?"

"He's been dialing for years!" cried Mr. Leonard.

"Ssssssh!" said Mrs. Leonard.

"Sorry," Mr. Leonard bowed to the wall. "My apologies."

"Paul, dear," said Mrs. Leonard, "what are you going to do while we're gone?"

"Oh—look through my microscope, I guess," said Paul.

"You're not going to be looking at germs, are you?" she said.

"Nope—just hair, sugar, pepper, stuff like that," said Paul.

His mother frowned judiciously. "I think that would be all right, don't you?" she said to Mr. Leonard.

"Fine!" said Mr. Leonard. "Just as long as the

pepper doesn't make him sneeze!"

"I'll be careful," said Paul.

Mr. Leonard winced. "Shhhhh!" he said.

Soon after Paul's parents left, the radio in the Harger apartment went on. It was on softly at first—so softly that Paul, looking through his microscope on the living room coffee table, couldn't make out the announcer's words. The music was frail and dissonant—unidentifiable.

Gamely, Paul tried to listen to the music rather than to the man and woman who were fighting.

Paul squinted through the eyepiece of his microscope at a bit of his hair far below, and he turned a knob to bring the hair into focus. It looked like a glistening brown eel, flecked here and there with tiny spectra where the light struck the hair just so.

There—the voices of the man and woman were getting louder again, drowning out the radio. Paul twisted the microscope knob nervously, and the objective lens ground into the glass slide on which the hair rested. The woman was shouting now.

Paul unscrewed the lens, and examined it for damage. Now the man shouted back—shouted something awful, unbelievable.

Paul got a sheet of lens tissue from his bedroom, and dusted at the frosted dot on the lens, where the lens had bitten into the slide. He screwed the lens back in place. All was quiet again next door—except for the radio. Paul looked down into the microscope, down into the milky mist of the damaged lens.

Now the fight was beginning again—louder and louder, cruel and crazy. Trembling, Paul sprinkled grains of salt on a fresh slide, and put it under the microscope.

The woman shouted again, a high, ragged, poisonous shout.

Paul turned the knob too hard, and the fresh slide cracked and fell in triangles to the floor. Paul stood, shaking, wanting to shout, too—to shout in terror and bewilderment. It had to stop. Whatever it was, it had to stop!

Palm Sunday, Welcome to the Monkey House

Palm Sunday, Welcome to the Monkey House